Cognitive-Behavioural Approach

Project Summary

|

Project Title: |

Project on Children and Adolescents at Risk Education (Project C.A.R.E.) |

|

Duration: |

2006-2011 |

|

Target Group: |

high-risk students in 52 secondary schools and 25 primary schools |

|

Project Objective: |

|

|

Collaborators: |

N/A |

|

Source of Funding: |

Quality Education Fund of the Education Bureau - Hong Kong Dollars 10,931,100 |

Theoretical Framework

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Previous researches had found that using cognitive-behavioural therapy as the theoretical framework for aggressors and victims group interventions is far more effective than other types of therapy, such as psychodynamic theory, behaviourism and cognitive therapy (Kazdin, 1987, 1995; Lochman, 1990; Lochman & Wells, 1996; McMahon & Wells, 1989; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000). Further, the director of the CARE Lab used cognitive-behavioural therapy to tailor the content of group intervention and found it to be very effective at reducing children’s aggressive behaviour (Fung,2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012; Fung, Gerstein, Chan, & Hutchison, 2011; Fung, Raine, & Gao, 2009; Fung & Tsang, 2006; Fung & Tsang, 2007; Fung & Wong, 2007; Fung, Wong & Chak, 2007; Fung, Wong, & Wong, 2004). For this reason, cognitive-behavioural therapy was used as the framework for group intervention in this project.

In ancient Greece, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus said that "people are not disturbed by things, but by the view that they take of them". It was not until the mid-twentieth century that Western psychologists systematically transformed this philosophy into psychological therapy. And further, Albert Ellis was one of the most influential founders of cognitive behavioural therapy (Ellis, 1962).

Ellis (1956) believed that humans have the ability to reflect and self-evaluate through retrospection and self-talk. Hence, people that have rational beliefs live logical and happy lives. In contrast, people with irrational beliefs experience negative emotions and behaviours. Researchers had utilised this concept in therapy programmes addressing adolescent aggressive behaviour (Guerra, Huesmann, Tolan, Van Acker, & Eron, 1995; Huesmann & Guerra,1997; Lochman & Dodge, 1994; Quiggle, Garber, Panak, & Dodge, 1992; Rabiner, Lenhart, & Lochman, 1990). Di Giuseppe and Kelter (2006) reviewed outcome studies and articles related to the effectiveness of Rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) and concluded that it is a well-suited treatment for aggressive children. Further, due to the psycho-educational nature of REBT, it is applicable to educational settings, and can also be applied to the family system of aggressive children, particularly parents. For these reasons, REBT is adopted as our major theoretical framework.

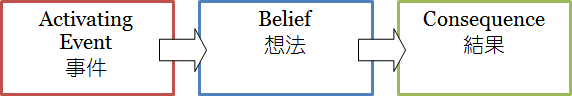

Through the A-B-C model, we could understand the cognitive processes behind students’ aggressive behaviour.

When an event (A) happened, the belief of an individual (B) about the event will lead to different consequences (C), including behavioural and emotional responses (Ellis, 1977). Therefore, if an individual held an irrational belief, it probably will lead to negative consequences. The following links are examples and explanations of various subtypes of aggressors’, victims’ irrational beliefs and their negative consequences. (To learn more about proactive aggressors and aggressive victims, please refer to Proactive Aggressors and Aggressive Victims).

Event (A): I was knocked down by a classmate during recess.

A student with a rational belief:

Belief (B): “He was just being careless.”

Consequence (C): It’s not a big deal. Get up and return to the classroom as though nothing has happened.

A proactive aggressor with an irrational belief:

Belief (B): “I have to let others know that I’m not that weak and I have the power.”

Consequence (C): Threaten the classmate and ask for compensation.

An aggressive victim with an irrational belief:

Belief (B): “Why pick on me and not other classmates? It’s his fault, and I have to retaliate and let him know that he is wrong.”

Consequence (C): Stare at the classmate angrily, and curse him quietly.

From the above examples, we can see that the individuals’ beliefs directly affect their emotional and behavioural consequences. Because aggressors and victims have cognitive distortions, their irrational beliefs cause deviant behaviour and negative emotions.

Moreover, Ellis (1977) discovered 12 types of irrational beliefs that cause deviations in people’s thinking, resulting in emotional distress and negative behaviour. The 12 irrational beliefs are introduced below, although interpretations of the irrational beliefs in group intervention vary in accordance with the characteristics of the two subtypes of aggressors and victims.

- It is essential that people must be loved by significant others for almost everything they do.

- Certain acts are awful or wicked, and people who perform such acts should be severely punished.

- It is horrible when things are not the way we like them to be.

- Human misery is invariably externally caused and is forced on us by outside people and events.

- If something is or may be dangerous or frightening, it is natural to be terribly upset and endlessly obsess about it.

- It is easier to avoid than to face life’s difficulties and self-responsibilities.

- We need something fundamentally other or stronger or greater than ourselves on which to rely.

- We should be thoroughly competent, intelligent, and successful in all possible respects.

- Since something once strongly affected our lives, it will affect our lives indefinitely.

- We must have certain and perfect control over things.

- Human happiness can be achieved by inertia and inaction.

- We have virtually no control over our emotions and we cannot help feeling disturbed about things.

These irrational beliefs reflect individuals’ personal values and views of life. If people’s lives do not match what they believe (i.e. their beliefs are irrational), they will doubt their own self-worth, become emotionally distressed and may do something to harm themselves or others. Workers will introduce the twelve irrational beliefs described by Ellis in the group intervention. Group members should gain a better understanding of the irrational beliefs underlying their behaviours and emotional distress.

Selected Publications

Fung, A. L. C., Gerstein, L. H., Chan, Y., & Engebretson, J. (2015). Relationship of aggression to anxiety, depression, anger, and empathy in Hong Kong. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(3), 821-831.

Raine, A., Fung, A. L. C., Portnoy, J., Choy, O., & Spring, V. L. (2014). Low heart rate as a risk factor for child and adolescent proactive aggressive and impulsive psychopathic behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(4), 290-299.

Fung, A. L. C., Gerstein, L. H., Chan, Y., & Hurley, E. (2013). Children’s aggression, parenting styles, and distress for Hong Kong parents. Journal of Family Violence, 28(5), 515-521.

Fung, A. L. C., Gerstein, L. H., Chan, Y., & Hutchison, A. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for Hong Kong students that engage in bullying. Revista De Cerecetare Si Interventie Sociala 42, 68-84.

Chan, J. Y. C., Fung, A. L. C., & Gerstein, L. H. (2013). Correlates of pure and co-occurring proactive and reactive aggressors in Hong Kong. Psychology in the Schools, 50(2), 181-192.

Law, A. K. Y. & Fung, A. L. C. (2013). Different forms of online and face-to-face victimization among schoolchildren with pure and co-occurring dimensions of reactive and proactive aggression. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1224-1233.

Fung, A. L. C. (2012). Group treatment of reactive aggressors by social workers in a Hong Kong school setting: A two-year longitudinal study adopting quantitative and qualitative approaches. British Journal of Social Work, 42(8), 1533-1555.

Fung, A. L. C. (2012). Intervention for aggressive victims of school bullying: A longitudinal mixed-methods study in Hong Kong. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 53(4), 360-367.

Fung, A. L. C. & Raine, A. (2012). Peer victimization as a risk factor for schizotypal personality in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Personality Disorder, 26(3), 428-434.

Raine, A., Fung, A. L. C., & Lam, B. Y. H. (2011). Peer victimization partially mediates the schizotypy-aggression relationship in children and adolescents. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(5), 937-945.

Fung, A. L. C., Gao, Y., & Raine, A. (2010). The utility of the child and adolescent psychopathy construct in Hong Kong, China. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(1), 134-140.

Fung, A. L. C., Raine, A., & Gao, Y. (2009). Cross-cultural generalizability of the reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire (RPQ). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(5), 473-479.